No German at the Met: 1917-1921 September 22 2023

In 1917, the Metropolitan Opera could hardly ignore the fact that the United States was at war with Germany, the homeland of the Richards Wagner and Strauss, and of many of the singers who sang their music. The German language would not be sung again from the stage of the Met until 1921, and although a few German works, including Parsifal and Tristan und Isolde, were offered in English translations, and Flotow’s Martha in its conventional Italian version, the loss of German opera to the repertoire severely enfeebled this international company.

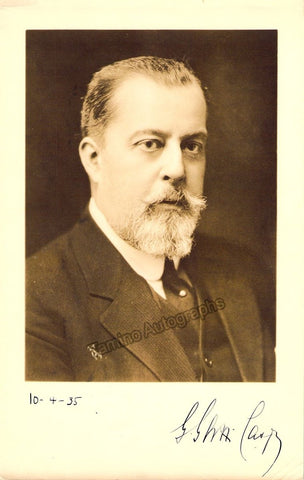

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Giulio Gatti-Casazza, the Metropolitan Opera Manager between 1908 and 1935.

The German Stage Society prohibited its members from accepting American engagements, and the 1917-1918 season had to be reorganized in the astonishingly speedy span of one week to accommodate the Met’s cancellation of the contracts of German nationals.

THE GADSKI SCANDAL

This process, in fact, had already begun the previous season when Johanna Gadski was not re-engaged after a distinguished Met career of seventeen years. A leading Wagner and Verdi soprano, Gadski was married to Hans Tauscher, a munitions agent tried (and acquitted) for anti-American espionage. Gadski’s reputation in New York was further compromised by an incident that occurred during a party at her home--bass Otto Goritz had the effrontery to toast the German cause and the sinking of the Lusitania, a disaster that helped precipitate the U.S. entry into the war.

THE VERSATILITY OF FLORENCE EASTON

In an effort to fill the void left by the absent German operas, the Met staged, in English, Liszt’s cantata Die Legende von der Heiligen Elisabeth. Found wanting in appeal, Elisabeth did not survive her initial season, but the artist who created her, soprano Florence Easton, proved to be one of the Met’s most versatile singers, persuasive in roles as diverse as the Gianni Schicchi Lauretta (she was its interpreter at the Met’s world premiere of the opera), Brünnhilde, Carmen, Butterfly, and Fiordiligi.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] English soprano Florence Easton (1882-1955).

FRENCH AND RUSSIAN REPERTOIRE

This was also the year of exotic novelties. The spectacle and the orientalisms of Henri Rabaud’s Mârouf were greeted with pleasure. The New York Sun praised the score’s “character, color, and exquisite fineness of texture.” In his debut season with the Met, Pierre Monteux conducted Mârouf and the American première of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Le Coq d’or. Boasting Willy Pogany’s fabulous décor, and given in the opera-ballet staging devised by Fokine for London and Paris, with dancers on the stage and singers in the orchestra pit, Rimsky’s opera achieved immediate popularity and was revived frequently until 1945, when it had its last Met performance.

A RIVAL OPERA COMPANY

The Philadelphia-Chicago troupe became an intermittent competitor rather than a friendly tenant when it took up residence at the last of Oscar Hammerstein’s opera houses in New York, the Lexington Theatre. Joining Mary Garden and many of her usual cohorts were Nellie Melba and dramatic soprano Rosa Raisa.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Polish soprano Rosa Raisa (1893-1963) shown as Basiliola in Montemezzi's opera "La Nave" in Chicago, 1921.

But it was the debut of a coloratura that caused the greatest sensation and a demonstration of the public’s approval even more delirious than the one that had greeted the arrival of Tetrazzini in 1908. Amelita Galli-Curci’s triumph as Meyerbeer’s Dinorah elicited 24 curtain calls after the aria “Ombre légère” and 60 at the end of the opera. Galli-Curci would enter the history of the Metropolitan before long.

THE DEBUT OF ROSA PONSELLE

Opening night of the 1918-19 season coincided with the signing of the Armistice in Europe on November 11. At the conclusion of the first act of Samson et Dalila, the cast assembled onstage with the flags of the victorious Allies and proceeded to sing their national anthems. Only four days later, the Met offered a new singer whose importance to opera in New York would far outweigh that of Galli-Curci. At the tender age of twenty-one, Rosa Ponselle made her debut on any opera stage and her Met debut in the company’s first performance of Verdi’s La Forza del destino, with Enrico Caruso and Giuseppe de Luca. The critics spoke of “splendid potentialities” and “vocal gold” but thought the young artist needed more refinement. In the barely twenty-year duration of her operatic career, Ponselle would display a quality of gold whose refinement has still not been matched. The fact that Forza was also a newcomer to the Met in 1918 seems astounding today, but at the time, some critics still expressed condescension towards Verdi.

PONSELLE AND WARTIME REPERTOIRE

Ponselle also accounted for the fiendishly difficult role of Rezia in the first Met Oberon. Though the Times reviewer found her a bit immature, particularly in deportment, he declared that Ponselle’s “scale is seamless, so equal are her tones from top to bottom.” The interdiction against the German language was still in force, but Weber had conveniently composed his opera to an English text.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] A gorgeous photograph of Rosa Ponselle, Enrico Caruso, and Jose Mardones in Verdi's "La Forza del Destino" at The Metropolitan, 1918.

THE DÉCORS OF JOSEPH URBAN

Joseph Urban designed the sets for Oberon, as he would for 53 other Met productions. The tireless Urban also worked consistently for other Broadway stages (he was responsible for Flo Ziegfeld’s extravaganzas and was architect of the wonderful, now vanished theatre that bore Ziegfeld’s name), and for the movies. Though sometimes diminished in their effect by the faulty execution of the set builders, Urban’s imaginative and stage worthy scenic plans guaranteed a high level of theatrical illusion at the Met. That is until fabric and paint became worn from overuse, season after season. Two generations of audiences knew such frequently presented operas as Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Faust, Madama Butterfly, Tristan, and many others, only in Urban’s versions.

The state of Urban’s faded, decaying productions was a constant reminder that the Metropolitan was a theatre inadequate to the demands of a repertory opera company. Since on-site storage facilities were virtually non-existent, the scenery had to be carted to and from warehouses all season long. Flats and platforms for the current performances were temporarily stacked against the outside wall of the building, right on Seventh Avenue, imperfectly protected by tarpaulins against New York’s harsh winters.

WORLD PREMIERES

The Met offered world premières of no less than five one-act operas during the course of the 1918-19 season. The cause of American music was not well championed by John Adams Hugo’s The Temple Dancer and Joseph Breil’s The Legend, the latter with Ponselle. Breil’s claim to posterity rests on the scores he provided for D. W. Griffiths’ films, The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. The progress of Puccini’s Trittico to the regular status it now enjoys in the world’s opera houses could not have been predicted by the qualified success accorded two of the three new operas. Puccini himself did not attend, but the Met provided luxurious casting.

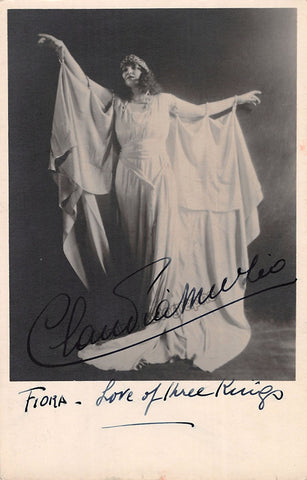

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Italian soprano Claudia Muzio as Fiona in Montemezzi's "L'Amore dei Tre Re"

Yet despite the strong portrayals of Claudia Muzio as Giorgetta and Geraldine Farrar as Angelica, Il Tabarro and Suor Angelica would wait many decades before returning to the repertoire. The wit of Gianni Schicchi was immediately appreciated and repeatedly displayed over the years when it was paired with diverse works--Pagliacci, L’Amore dei tre re, La Bohème, and Elektra--before settling on a brief marriage with Salome!

CARUSO AND FARRAR

The Met’s most potent box office attractions, the Neapolitan tenor and the Massachusetts soprano, still retained their powers to animate works that languished when performed by lesser artists. In a revival of Fromental Halévy’s La Juive Caruso found a role in which he was praised as much for his acting as his singing. In Zazà, Farrar’s natural penchant for the sensational was enhanced by director David Belasco’s provocative suggestion that the demi-mondaine heroine spray perfume on her panties in full view of the audience. Although Leoncavallo’s score was dismissed for the banality of its tunes, the opera was performed 20 times in the three seasons Farrar was there to sing it.

[IMAGE] Italian star tenor Enrico Caruso and American soprano Geraldine Farrar in Charpentier's opera "Julien" at The Met premiere on February 26, 1914.

Zazà’s initial popularity far eclipsed the tepid reception received by the first staging in America of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin (in Italian), with Muzio, Giovanni Martinelli, and Giuseppe de Luca, dismissed by one reviewer as “weak, pretty, inconsequential.” Onegin would wait nearly 40 years before entering the Met repertory on a regular basis.

CHICAGO'S STARS

The five-week 1919-20 season of the Chicago opera company at the Lexington had its usual share of the scandalous and the phenomenal. For the Times reviewer, Camille Erlanger’s Aphrodite, for Mary Garden of course, was “not pleasant to the eye of decency or to the ear, either.” But it was the performance of an old standard that nearly caused a riot when police were summoned to control an unruly crowd, desperate to hear Titta Ruffo, Tito Schipa, and Amelita Galli-Curci in Rigoletto. At this point in her career, Galli-Curci’s popularity was not affected by critical comment on her faulty intonation. The soprano would wait until 1935, near the end of her singing days, before undergoing an operation to remove the throat goiter she knew was causing the difficulty, preferring wayward pitch to the possibility of losing her voice altogether.

THE DEATH OF CARUSO

The health problems of the world’s greatest tenor were of a more serious nature, and they became alarmingly apparent to everyone not long after his final opening night in La Juive, on November 15, 1920. At his first Pagliacci, on December 8, Caruso strained his side while singing “Vesti la giubba.” He was said to be suffering from simple neuralgia.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Caruso in happier days -an interesting photograph of the star tenor surrounded by other fellow singers in Havana, Cuba, 1920.

But on December 11, during a performance of L’Elisir d’amore at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the beloved singer began to cough up blood. He continued to voice the opera-buffa woes of Nemorino as he dropped bloodstained handkerchiefs into a well that was part of the décor. At the conclusion of Act I, the audience was informed that their favorite was ill but willing to continue. A chorus of “nos” mercifully curtailed the show. After three more appearances, Caruso was gone forever from the Met, in fact from opera. He returned to Italy to recuperate from what was diagnosed as pleurisy, but died at the age of 48 in Naples on August 2, 1921.

GIGLI, MARTINELLI, LAURI-VOLPI

Certainly, no single singer was more closely identified with the Metropolitan than Caruso, and more central to its fortunes. He was irreplaceable. But with the providential arrival of Beniamino Gigli (in Mefistofele), the company had acquired what many now consider the most beautiful tenor voice of the epoch, perhaps even of the century. The dulcet sound of Gigli more than compensated for a style that was sometimes unrefined and for a stance and posture that addressed adoring fans in the theatre rather than the opera’s dramatic requirements. Gigli took over Andrea Chénier, a role meant for Caruso, in the Met’s first production of Giordano’s opera. Gigli and the always improving, ever stalwart Giovanni Martinelli were star tenors of the first magnitude, and would soon be joined by Giacomo Lauri-Volpi. So, despite the loss of Caruso, the Met could hardly be described as “tenor poor” in the ‘20s.

[IMAGE] Ettore Panizza, Giulio Gatti-Casazza, Giovanni Martinelli, Walter Damrosch, and Rosa Ponselle among others

Martinelli was the first Don Carlo in the Met’s history, but Verdi’s opera was considered only a “success of curiosity.” According to the New York World, the music, of what later generations would consider one of the composer’s masterworks, went “from the sublime to the trivial.” With casts that included Ponselle and, in later performances, Feodor Chaliapin, Don Carlo eked out a mere13 performances in three seasons until its triumphal return to the Met in 1950.

THE MET, AGAIN “AUF DEUTSCH”

In the 1919-1920 season, one year after the end of the Great War, the management had cautiously begun to reintroduce Wagner with Parsifal, but in English. It was only in Fall 1921 that the company would return German opera to its rightful place in the repertoire, coincidental with the debut of Maria Jeritza in Erich Korngold’s Die tote Stadt. The Moravian soprano immediately became one of the company’s most valuable assets and remained so for more than a decade.

SEE ALSO

- Enrico Caruso Autographs & Memorabilia

RELATED BLOG ARTICLES

Interested in authentic autographs?