Marston Records - A Story November 07 2023

MARSTON RECORDS IS NOW 26

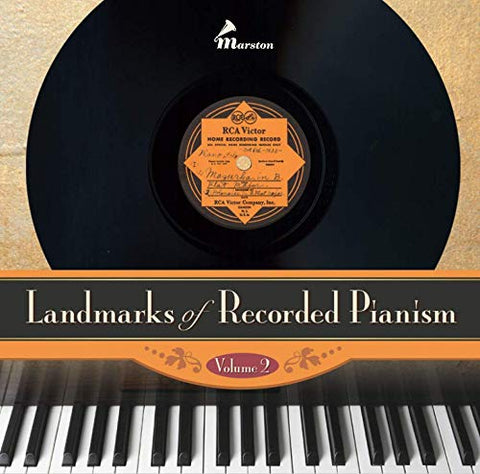

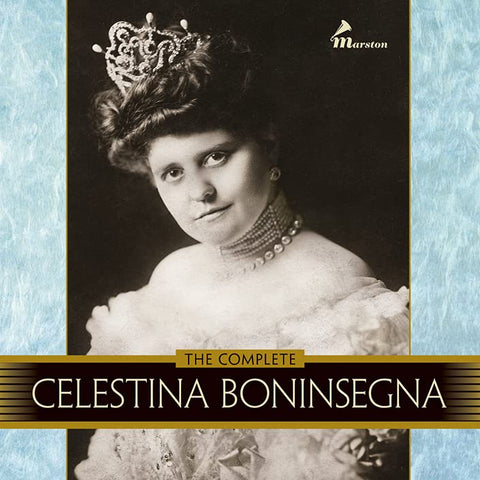

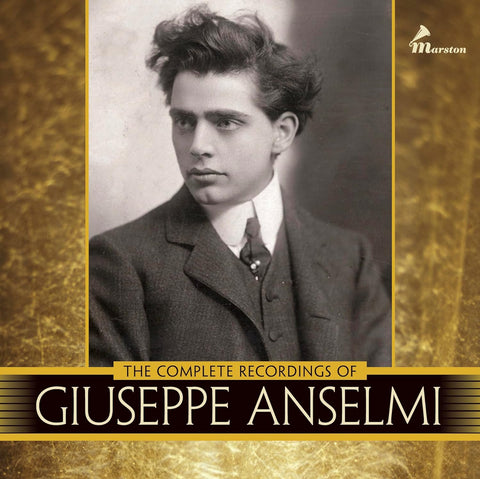

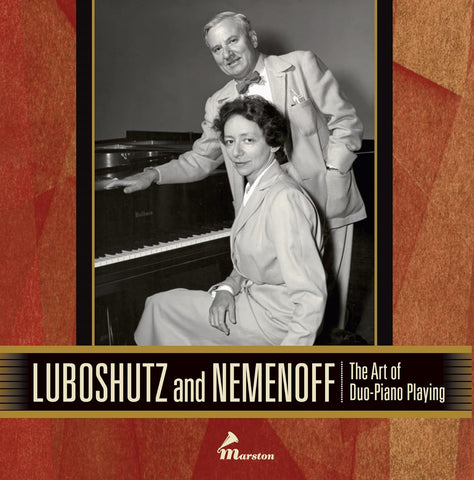

Scott Kessler and I founded Marston Records in 1997, so it is now twenty-six years old. Starting the label was a natural extension of the audio restoration work I had been doing since 1976, remastering historic recordings of musical performances reissued by labels such as Columbia, Desmar, Koch, Biddulph, Romophone, and RCA/BMG. Scott and I felt we could make a significant contribution to the field of historic reissues by featuring singers and pianists whose names were too esoteric for other labels to even consider, as well as by issuing sets of the complete recordings of star artists.

MARSTON'S PREDECESSORS, A EUREKA MOMENT AND NO PUBLICATION SCHEDULE

The Pearl, Romophone, and Biddulph CD labels were pioneers in the field, but by 1997 those labels were all but moribund. Scott had a Eureka moment, realizing that we could start our own company and continue in this vein, while concentrating on quality by not adhering to a strict publication schedule. Since the beginning our modus operandi has been to keep a number of projects simultaneously simmering at different rates on the front, middle and back burners. Working in concert with a small group of knowledgeable colleagues – collectors, musicologists, writers, and musicians - we have produced more than 130 multi-CD projects some of which have taken five or even ten years to reach completion.

OBTAINING OPTIMUM SOURCES A KEY ELEMENT -INDEBTED TO COLLECTORS- CONTEXT IN ESSAYS - DESIGN

While seeking to locate optimum audio sources for our projects, we also work to secure interesting photos of the featured artists. We are indebted to many avid record and photo collectors - their unstinting generosity has gone beyond anything we could ever have expected. Equally important as presenting recordings in the best possible sound is the necessity of providing essays which give historical and musical context. A project is never complete for Marston without such an essay, and we engage writers who have a solid grasp of the subject at hand. Also, important has been the fact that, from the beginning, all of our booklets have been designed by one artist, Takeshi Takahashi, who has given them a distinctive and excellent design element, setting Marston Records apart from every other reissue label.

SCOTT'S BACKGROUND AND ROLE AT MARSTON

Much of the success of our company is due to my dear husband and business partner, Scott Kessler, whose vision it is that keeps us always moving forward. He works hard and long for Marston Records, and has been doing so from the beginning, taking care of absolutely everything besides audio restoration and artists and repertoire planning. Scott grew up in Chicago and graduated from the University of Michigan with degrees in mathematics, sociology, and art history. After graduation, he worked for a small chamber music festival in Mount Gretna, Pennsylvania, soon becoming its general director. After six years he became the general manager of the Pennsylvania Opera Theater. We met in 1993, and by 1997 Scott felt that we could use his financial and artistic experience, with my abilities in restoring historical recording and my background in music, to launch our own classical music CD label. The idea of actually doing such a thing was beyond my wildest imaginings. I had always worked for other record labels, having not the slightest idea of how to run any business. Over the past twenty-six years, Scott has kept me centered while coming up with innovative strategies for increasing our customer base. His ability to keep us going is amazing, for we are as close to “non-profit” as a business could be.

WARD'S ROLE

My role at Marston Records is as a co-producer, as well as the audio restoration specialist for all projects. My avid record collecting had prepared me in a different way from my career as a musician, and for better or worse, I am the one who chooses which artists to reissue, and my record collection has served as the basis for many of our issues. I am not an audiophile, and my interest in high end gear extends only to possessing the proper equipment for my audio preservation work. I am fortunate to have been blessed with an excellent ear for music, and while I love using digital technology for my work, it is the music that ultimately consumes my interest, and my ears are always my guide and final arbiter. Some have labelled me an audio engineer, but I don't care for that appellation, for my approach to audio work is far more subjective than scientific, and perhaps even artistic.

BLINDNESS AND MUSICAL PROCLIVITIES

To explain how I fell into the work that has been my passion for nearly fifty year: I was born in 1952, premature by two months, so I was placed into an incubator where I was given more oxygen than needed. It damaged my optic nerves and caused my total blindness. I was nurtured by loving parents, who were not musical but loved both classical and popular music. My earliest memories are hearing classical music on the record player, which I insisted on hearing over and over again. My mother played a bit of piano, and I loved hearing her play. By the time I was four or five, she had taught me the notes of the scale and how to play simple chords. I spent happy hours at the piano listening to the sounds that different chords made, teaching myself how to play hymns from church and pop tunes I heard on the radio. I began piano lessons at six, but never applied myself, always preferring to play by ear.

RECORDS CONSTANT COMPANIONS - STOKOWSKI AND LIVE CONCERTS

Indeed records were my constant companions. This was a time when 78s were being replaced by LPs, and relatives and friends gave me their cast off 78s, including a huge number of single sided Victor records of opera singers and instrumentalists such as Caruso, Melba, Schumann-Heink, Tetrazzini, Kreisler, de Pachmann and Rachmaninov. One friend gave me a substantial collection of 1930s Victor sets of Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra. I devoured the music, and got to know every disc. At the same time my parents began to take me to Philadelphia Orchestra concerts, and I was especially thrilled to hear Charles Munch and Leopold Stokowski as guest conductors.

So it was that at an early age I began to have the sound of live music in my head, and at the same time I was also gradually realizing that my old records showed that there was something different and extraordinary about the way music was played during the first forty years of the century, that era which many consider to be the "golden age" of romantic music performances.

TAPE RECORDING, RADIO SHOW, HIS FIRST EQUIPMENT - ADMIRES THE WORK OF ANTHONY GRIFFITH

When I was eleven my parents gave me a tape recorder, and recording many of my 78s onto tape became my favorite pastime. During my years at Williams College, I became a disc jockey on WCFM radio. i presented both classical music and jazz programs. As an experiment, I decided to broadcast some of my orchestral 78s. Listeners seemed to enjoy it and I continued to do that. Keith Bauer, a close friend from high school who eventually became an acoustics engineer for Bell Labs, built a high-quality preamplifier and a graphic equalizer for me so that I could try to improve the sound of my 78s when playing them on the air. My goal was to make them sound natural without worrying too much about the defects. I learned to splice tape to remove some of the obtrusive clicks and pops, and worked with the equalizer, teaching myself how to improve the overall sound of the records. I didn't know very much about remastering old records, but I also owned many LPs of 78rpm reissues - I could hear that some were faithful to the 78s, while others were extremely amateurish and poor. Some of the remastering work on EMI reissues was extremely good, with many of their best reissues remastered by Anthony Griffith, whose work I have always revered.

JAZZ AND CLASSICAL - CAREER AS A JAZZ PIANIST - RECORD COLLECTING

During my teens, all my allowance money went toward buying old records as well as new LPs at thrift and other stores, not just classical music but also lots of jazz records of Art Tatum, Fats Waller, Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, and many others. I was just beginning to gain some modest ability and confidence as a fledgling jazz pianist. I was employed during several summers playing at a resort in the Pocono mountains, working in a quartet with experienced musicians who all took me under their wings and taught me more than I could ever have learned on my own, giving me the experience to form my own band after college. Soon I was successful and earning money from playing jazz dates. Over time I became a major collector of original historical recordings.

BROADCASTS STOKOWSKI RECORDINGS IN PHILADELPHIA - DISCOVERS GREAT PIANISTS OF THE PAST AND A NEW WORLD OPENS

I returned to Philadelphia after college in 1972, and in retrospect I now realize that the timing was just right for me to find my way into the audio restoration business. After decades of slumber, worldwide general interest in old recordings began to awaken. My amateur work with old records caught the notice of several radio broadcasters in Philadelphia. Soon I was invited to produce a fifty-eight hour-long program series where I discussed and played every recording that Stokowski had made with the Philadelphia Orchestra, from the first in 1917 to 1940, with most of the records coming from my own collection. In preparation for one of the programs, I contacted Gregor Benko, co-founder and de facto curator of the International Piano Library (IPL), asking to record an interview about Rachmaninoff and Stokowski. After we finished, I stayed for several hours listening to some of the great records of pianists whose names I barely knew. I won't ever forget that day because it was as if an entire new world had opened to me.

THINKS HE COULD DO BETTER THAN RCA AND IS GIVEN THE OPPORTUNITY

During the visit to IPL, I mentioned that I had purchased the 15 LPs on RCA of the complete recordings of Rachmaninoff, which Gregor Benko had helped to produce. I told him how much I loved the performances but that I found some of the remastering (done at RCA by Jack Pfeiffer) disappointing. Benko asked sharply, "Well, do you think you could do better?" I thought I could. He gave me a few 78s to take home and asked me to give them my treatment. Apparently, he liked what he heard because he soon asked if I could do all of the remastering for some planned IPL LPs slated to be issued on the Desmar label. This lead to my being hired by CBS to remaster 8 LPs of vintage 1930s Budapest Quartet recordings.

A GOOD REVIEW AND A BAD ONE THAT ACTUALLY HELPED

As a twenty-four old novice with no experience, I felt ten feet tall reading the favorable review in High Fidelity magazine but was brought up short by a scathing review in the Association for Sound Recordings Journal, comparing my work unfavorably to that of Anthony Griffith, who had remastered some of the same material for EMI Classics. Clearly, this critic knew the original 78s and felt that I had applied too much filtering which degraded the sound. Although I was hurt, I took the review to heart, making my own comparisons and realizing that the criticism was justified. I realize now that this review helped me greatly to improve my skills when I most needed guidance. It now seems to me that very few current reviewers have this kind of direct awareness of what original 78s sound like, and therefore I find reviews of the remastering work on reissues to be constructive only occasionally.

THE RESPONSABILITY OF RESTORATION SPECIALISTS AND REISSUE COMPANIES

More historical performances are made available now than ever before, and there are multiple competing versions of the same historic recordings. Few today know much about the earliest forms that recordings took and how they were made prior to the appearance of vinyl LPs in the 1950s. Fragile wax cylinders, and shellac and acetate discs that play at 78rpm, are practically unknown, and few have any concept of how historic recordings actually sound. Reviewers, sadly, cannot be relied upon for a genuine assessment of competing restorations. I believe this is mainly because of their lack of familiarity with original sources. That is why it is essential that digital restorations of historic recordings be made with the utmost care, background and knowledge. Digital technology has given us extraordinary tools that can either improve or degrade the sound of historic recordings, and it is our responsibility as restoration specialists to be faithful to the original sound sources. With the availability of various competing digital restoration computer programs, almost anyone can produce their own “restorations” of old recordings without knowledge of the original, and many do just that. Searching various YouTube channels, I find some excellent work, while other versions are either hideously over-processed or sound as if the restorer had made little or no effort to locate good copies of the original sources.

THE MOST IMPORTANT FACTOR

The most important factor in making a faithful digital restoration is the very first step, which is to try to obtain perfect examples of primary sources. When I begin a project, my greatest amount of time is spent searching for such sources if they are not already in my own collection: wax cylinders, shellac discs, instantaneous transcription discs, or recordings after 1950 recorded on magnetic tape. In the early days of recording, cylinders and discs were cut with different types of grooves, and it is extremely important that those recordings be played with the correct size stylus. I own many sizes of styli, and achieving optimum results often requires laborious experimentation with these. Once I have made a satisfactory transfer, I use digital software only to the point of improving the recording by correcting pitch instability, balancing the sound, and removing unwanted clicks, pops, and general noise that masks the sound of the music. I avoid at all cost invasive tampering for its own sake.

CURRENT TECHNOLOGY AND THE FUTURE

As time proceeds, I worry that original sources will become increasingly difficult to locate and for all purposes, unavailable, and that many resultant poor quality, amateur restorations will be ingenuously accepted as honest representations of those originals. Current technology allows us to manipulate the essence of a performance, thereby distorting it. Now we can, if we so choose, increase the tempo of a performance to give it added excitement; likewise, we can correct the faulty pitch of a singer or change a pianist's wrong note. But is that right? I think not. If there is speed instability in a recording, technology should most certainly be employed to correct it so that the integrity of the original performance is preserved. But to use a computer to change the artist’s tempo seems like dishonesty, although I have to admit that I have been tempted to engage in such jiggery-pokery, even if it is just for my own amusement. Future technological advances will offer ever more possibilities for distorting the honesty of old recordings, and we keepers of the flame must avoid using our tools irresponsibly towards such ends.

COMPACT DISCS PREFERRED BY MARSTON CUSTOMERS

I am now seventy-one, but with luck, I hope that I will be able to continue making historic recordings available even as current technology gives way to new forms of dissemination. When I began nearly fifty years ago, the long-playing vinyl disc was the preferred playback medium, but by the late 1980s the vinyl record had been superseded by the compact disc, with the majority of my work made available on CDs. But now, thirty-five years on, it is clear that the compact disc will soon become an obsolete medium that is supplanted by digital downloads. This has already occurred for popular music of all genres, but for classical music, the CD is still preferred by many enthusiasts, and our company continues to produce our historical reissues in this format, with booklets comprising thorough documentation and extensive essays accompanied by rare photographs. There is something about having that physical object in one's hands that our loyal customers find far more appealing than having the material on a computer.

WE ARE PROUD

Scott and I are duly proud of what we have accomplished since 1997, producing reissues that brought to light astonishing great historic perfo-rmances, many of which would otherwise remain unknown and unavailable. We have preserved and disseminated rare and important recordings by little known pianists and singers, as well as famous artists such as Josef Hofmann, Joseph Lhevinne, Feodor Chaliapin, John McCormack, Rosa Ponselle, Emma Calvé, and Lotte Lehmann. One set that I believe stands out among all of our projects is "The Dawn of Recording", a three-CD collection featuring some of the earliest ever recordings of classical music, made during the 1890s on wax cylinders. They sound very primitive, but they prove that music was performed differently in those days before the era of commercial recording. Listening to those fascinating documents opens a window on nineteenth-century performance practice, perhaps bringing us in closer communion with the composers of that era. Who knows if the actual cylinders will survive, but we can feel certain that our CDs will help to preserve the sound captured on them. We invite you to peruse our website where you can read the contents of all of the printed material that accompanies our CD sets. Please enjoy!

https://www.marstonrecords.com/

Ward Marston during a Broadcasting Session

OTHER RELATED BLOG ARTICLES

- The Mapleson Cylinders: The Met Opera Live 1900-1903

- Larry Holdridge's Historical Records Collection

Interested in authentic autographs?