Beethoven Hair: In Search for the Truth October 06 2023

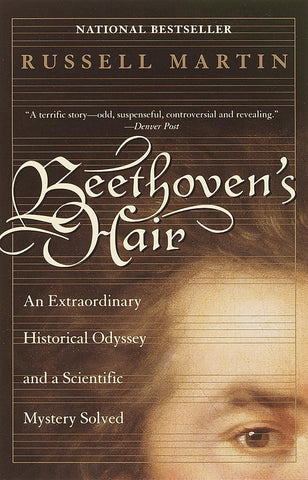

Reality may often be weirder than fiction, with more planning and rifer with an accident that could be envisaged in a composition generated only by the mind. One example of this aspect is Russell Martin's Beethoven's Hair: An Extraordinary Historical Odyssey and a Scientific Mystery Solved. Some components may shake even the most unshakable idea of fiction in this story. Russell Martin's eloquence and rigorous investigation are part of what makes it work here. Martin connects the dots for us in a way that makes sense and brings everything to life. In some ways, this story is building to a conclusion.

One of the essential components is first to define Beethoven's life, who was regarded as contending with his great progenitors, Haydn and Mozart, at the outset of his career, by exploring new routes and constantly increasing the depth and span of his work. The first and second symphonies, the first six string quartets, the first three piano ensembles, and the first twenty piano sonatas, including the well-known Pathétique and Moonlight, are among the early era's most important works.

Many of classical music's most renowned compositions were created after Beethoven's deafness crisis, noted for their large-scale works of heroism and battle. The works from the middle era include six symphonies, the final two piano concertos, a triple concerto, and his lone violin concerto. Fidelio's lone opera, five string quartets, and seven further piano sonatas, including Waldstein and Appassionata.

Beethoven's late period began in 1816 and lasted until 1827 when he died. His Late works are highly regarded and are differentiated by intellectual heft, intense affirmation, and highly individualistic and conducting experiments with forms; for example, the crisp C quartet has seven movement patterns, whereas his more famous Ninth Symphony adds choral force to the orchestra in the final movement. This stage includes Missa Solemnis, the final five string quartets, and the final five piano sonatas.

Before he died, he addressed a letter to his brothers, requesting them to investigate why his health had been so bad for so long regardless of the numerous hospital visits to seek health services. The Will of Heiligenstadt can be found in this letter. The Will, which is named for the Danube hamlet in which it was written, provides a unique look into Beethoven's spirit. He still wanted to determine what went wrong and, most importantly, what could be done in the future to prevent similar issues from happening to other people.

He suffered from various diseases, as did many men in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Beethoven's list includes chronic stomach discomfort and diarrhea caused by inflammatory bowel illnesses, depression, alcohol misuse, respiratory issues, joint pain, eye inflammation, and liver cirrhosis. This latest issue might be the final domino to fall, given his enormous drinking habit.

A lock of Beethoven´s hair, sold in auction in 2016 for over USD$15,000

After being bedridden for many months, he died in 1827, most likely from the liver and renal dysfunction, peritonitis, abdominal ascites, and encephalopathy. An autopsy indicated significant cirrhosis and ear dilatation of the auditory and other nerves. This sort of Jewish refugee, probably a relative of Ferdinand Hiller, either provided Dr. Fremming the lock of Beethoven's hair or used it as a fee.

There are now answers to the questions asked about 200 years ago from the desire to know what was wrong. Furthermore, it originates from an odd source: Beethoven's hair. Many individuals trimmed Beethoven's famed hair immediately after his death.

One of that hair, chopped by a teenager, has amazingly survived. Ferdinand Hiller, a 15-year-old violinist, grabbed a piece of Beethoven as a memory of the talented but irascible composer. Hiller, who became a composer and conductor, encased his prize in a locket and presented it to his son, Paul. The younger Hiller's handwritten description recognized the item. The narrative of the locket's journey from Vienna to the United States is remarkable. Perhaps he bought safe passage for a Jewish family during the Holocaust.

A couple of Beethoven fans banded together in December 1994 to bid for a lock of the master composer's hair at a Sotheby's auction in London. They had no plan: no ideas of DNA testing or the like came to mind. They thought that a lock of hair from one of the greatest composers who had ever lived, with perhaps one of the best minds that had ever controlled gray matter, was up for auction. They would come to possess a genuine part of the composer, who meant so much to each of them by combining their money. Ira Brilliant, who had located the artifact in the Sotheby's catalog, was excited when they won the auction for around $7,300.

Guevera and Ira Brilliant then discover what caused Beethoven's deafness. They are threaded with brown, gray, and white threads to perform imaging, DNA, chemical, forensic, and toxicological studies. There was no indication of morphine, mercury, or arsenic.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Original etching of Beethoven by artist Arthur Heintzelman (1891-1965), published in an edition of only 200 exclusively for the members of the miniature print society, 1943.

Still, an exceptionally high lead level, most likely because of chronic lead poisoning, might have caused Beethoven's deafness, which could not be explained through many of his other issues. Other research indicates that he drank from a lead-containing cup. It is also worth noting that wines from this era frequently contain lead as a sweetener.

Beethoven's private lifestyle became complicated. Around 28, he became deaf, prompting him to ponder suicide. He became lured to unreachable (married or aristocratic) ladies; he never married. His first indisputable love affair with a diagnosed lady began in 1805 with Josephine Von Brunswick; most scholars believe it ended in 1807 because she could not marry a commoner without losing her children. In 1812, he penned a lengthy love letter to a woman referred to only as of the Immortal Beloved. Several candidates were proposed, but none got widespread support.

Some students believe Beethoven's poor productivity from around 1812 to 1816 was caused by sadness due to his realization that he would never marry. Beethoven frequently quarreled, frequently fiercely, with his loved ones and others (including a complex and public custody battle over his nephew Karl); he often treated various people poorly. He moved frequently and had typical non-public behaviors, such as wearing filthy clothing while washing constantly.

Nonetheless, he had a close and loyal network of friends. Many listeners hear an echo of Beethoven's life in his music, which frequently depicts battle accompanied by way of triumph. This term is frequently applied to Beethoven's introduction of masterpieces in the face of his severe personal struggles.

In the review of the cause of the deafness and the death of Beethoven, there were clues of lead poisoning from the strand of hair. Beethoven's claim was poisoned with lead, much alone killed by Dr. Wawruch's acts, appears to be based on dubious experimental evidence examined using shaky assumptions. As well as arbitrary, Beethoven's medical record was incongruous with deadly lead poisoning, notwithstanding solid doubts regarding the interpretation of prospective consumer profiles.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Unsigned Carte-de-Visite with a portrait of the Bonn genius, an original CDV by Neurdein, Paris.

While the early symptoms of lead poisoning are often non-specific, the patient's central nervous system eventually becomes involved. These include paralysis, blindness, and dementia; however, Beethoven shows none of these symptoms. On the other hand, Beethoven's symptoms were entirely compatible with the course of liver illness in the later years of his life.

Due to Beethoven's renown and the number of prominent contemporaneous sources, his medical history can be summed up in fantastic detail. Beethoven's physicians' reports, discussion notebooks that his deafness compelled him to use since 1818, and eventually, Beethoven's letters to friends and family and the memoirs they penned are among them.

A pretty detailed picture of the progression of Beethoven's deafness may be gained by searching through these sources for references to Beethoven's hearing impairment and other ailments and his dietary habits. Pathologists Bank and Jesserer compiled perhaps the most comprehensive collection of these remarks into an excellent compendium and their annual report on Beethoven's terminal condition.

Beethoven's symptoms, such as jaundice, indicate that he contracted viral hepatitis. His continued consumption of significant quantities of wine, beer, and spirits probably hastened the progression of his liver disease. As was his custom, he ignored his doctors' directions. After all hope of recovery had faded, his physicians allowed him to drink alcoholic sorbets, which provided him with considerable relief. However, historical data indicates that Beethoven was not an alcoholic.

During the last five years of his life, his condition rapidly deteriorated, and there were rising indicators of hepatic failure, which ultimately led to his death. Dr. Wagner conducted an autopsy one day after Beethoven died, and his report depicts cirrhosis and liver atrophy, as well as other symptoms (such as splenomegaly and pancreatitis) that are typically associated with complex and persistent liver illness.

Sviatoslav Richter signed LP record of Beethoven's Piano Sonatas Nos. 9 & 10

The book Beethoven's Hair concentrates on Brilliant's endeavor to record his whole treasured relic trip. Much of the book is devoted to locating the medallion's bearer, who might be a descendent of Hiller, one of the Jews who fled the Nazis to Sweden via Denmark. Kay Fremming, a Danish doctor, assisted the refugees, and his family verified that one of them presented him with a medal as a thank you. Martin describes the escape of Jews to Denmark, leading the reader to a church in the town of Gillejele, where a group seeks sanctuary as a Gestapo official knocks on the door.

The obsessive Brilliant works incredibly hard on his inquiry, but he can never make the connection between both halves of recorded history and his hair. No worries. The lock's origins are never revealed, and it is not a one-of-a-kind artifact: other locks of Beethoven's hair can be found at the Library of Congress, the University of Hartford, the British Library in London, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, and the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, Germany, according to the Beethoven Center. Many people who came to see the corpse, including Huttenbrenner, removed the padlock as a souvenir. According to Martin, by the time unfortunate Ludwig was laid to rest, his head seemed to have been chopped off with scissors.

The prospect of finding out what hair testing has revealed is likely to keep the reader reading Beethoven's Hair until the finish. The media reported in 1996 on the astounding revelation that the initial set of testing revealed no trace of drug usage. Many think he took morphine or another narcotic to alleviate the discomfort of his condition, particularly near the end of his life.

Martin believes that if he has denied sedatives, which is not the only plausible rationale for the rejection, he likes to maintain his mind as straightforward as possible to continue. That type of thinking matches Beethoven's image, at least from today's perspective, of the hero who does not use drugs.

The second set of heavy metal traces testing revealed normal levels of most substances, including mercury, high levels of which would have confirmed the widely debated hypothesis that Beethoven had and was treated for syphilis, another blot a hero cannot afford. However, the tests did uncover something new: very high lead concentrations, 42 times those of control samples.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Photo engraving of Beethoven in his study, from early 20th century.

This discovery, made public earlier this month, clearly indicates that Beethoven was enormously poisoned with lead at his death, maybe for dozens of years previously. Many of the composer's ailments, from gastrointestinal pain to hearing loss, might be attributed to lead poisoning. The likely explanation for his conduct is even more fascinating, considering that lead poisoning symptoms are irritability, forgetfulness, and unpredictable behavior.

Martin claims that even his peculiar walking style demonstrates the consequences of persistent lead exposure. Another question is why Beethoven had high amounts of lead in his body, although Martin believes lead was in the foods or even leaded wine, which has added to minimize bitterness.

There were many thoughts about what could have gone wrong. The great composer died in 1827 after suffering for decades from a disease that took the most of his life. Researchers do not know why his lead levels were high, but they were. According to Bill Walsh, some thoughts: Other possibilities led a team investigating samples of Beethoven's hair and skull bones at the Department of Energy facility in Argonne, Illinois.

The composer enjoyed wine, and at the time, wine was known to contain significant quantities of lead. According to Walsh, he also drinks from a cup that includes some lead and visits a spa where he drinks mineral water. However, according to Walsh, Beethoven may not have been exposed to above-average lead levels. The composer's body might have been lead-sensitive and unable to eliminate it. Walsh argues that the hair and bone samples studied belonged to Beethoven since they originated from two different sources and were matched through DNA testing.

One of the book's most significant principles is never to give up. Beethoven's resilience in the face of hardship is one of his defining characteristics. Many people know that Beethoven began to lose his hearing when he was 30, and he stated in a letter to a friend at 30 that his hearing had steadily diminished over the last three years of his life.

Although he could make light of his other health issues, Beethoven's loss of hearing was so severe that he lost the capacity that permitted him to operate in his company and listen to music. Despite his depression, the great composer toiled relentlessly, composing some of his finest compositions while fighting this dreadful condition. On May 7, 1824, his Ninth Symphony was performed in public for the first time in Vienna. Although Beethoven was present and acting as conductor, he heard nothing, and thus the musicians were led by a different person.

[CLICKABLE IMAGE] Program cover for a gala performance of Beethoven's opera "Fidelio" to commemorate his Centennial at the Berlin Staatsoper, 1927, conducted by Bruno Walter.

From those days, it is clear that the technology that made some of these discoveries back in the day was minimal. The industrialization era began, and most work was still being done manually. That also means that they had little equipment that they could have used to measure or conduct analysis for some of the critical aspects, which is also why the central issue of Beethoven's illness was not well known.

The hairs had to be preserved for a later date, which was not known when that would be. However, his prowess in music and arts and his letter requesting the study to be conducted also made it prudent to determine where the challenge was.

Without some of the most advanced technologies present currently and bearing in mind the time when Beethoven was alive, getting information using the standard methods cannot work. It has taken over 200 years to finally get the answers to what made Beethoven ill due to the lack of technology.

That shows the importance of the involvement of science and the advancements that have taken place over the years. After conducting the tests, the results need to be analyzed and interpreted from a scientific standpoint, which is crucial to ensure that one can quickly determine some aspects, such as the distribution of the lead in the body.

References:

"Beethoven's Hair" by Russell Martin

RELATED BLOG ARTICLES

- Autograph Collectors of the Past: Louis Koch

- Our Visit to Beethoven´s Birth House in Bonn, Germany

Interested in authentic autographs?

SIGN UP for TAMINO AUTOGRAPHS NEWSLETTER